Where Did Kathe Kollwitz Study or How Did She Learn Art

| Käthe Kollwitz | |

|---|---|

Käthe Kollwitz, 1919 | |

| Born | Käthe Schmidt (1867-07-08)8 July 1867 Königsberg, Prussia, Northward German Confederation |

| Died | 22 April 1945(1945-04-22) (aged 77) Moritzburg, Saxony, Germany |

| Resting place | Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde |

| Nationality | German |

| Motion | Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | Karl Kollwitz |

| Children | ii (including Hans) |

| Relatives | Johanna Hofer (niece) Maria Matray (niece)[one] |

| Awards | Cascade Le Mérite 1929[2] |

Käthe Kollwitz (German pronunciation: [kɛːtə kɔlvɪt͡s]; born as Schmidt; 8 July 1867 – 22 April 1945)[iii] was a German creative person who worked with painting, printmaking (including etching, lithography and woodcuts) and sculpture. Her almost famous fine art cycles, including The Weavers and The Peasant War, depict the effects of poverty, hunger and war on the working grade.[4] [5] Despite the realism of her early on works, her art is now more closely associated with Expressionism.[6] Kollwitz was the commencement woman not merely to be elected to the Prussian University of Arts but also to receive honorary professor condition.[vii]

Life and work [edit]

Youth [edit]

Kollwitz was born in Königsberg, Prussia, equally the 5th child in her family. Her father, Karl Schmidt, was a radical Social democrat who became a mason and business firm builder. Her female parent, Katherina Schmidt, was the daughter of Julius Rupp,[8] a Lutheran pastor who was expelled from the official Evangelical Country Church and founded an independent congregation.[ix] Her education and her art were greatly influenced past her grandfather'due south lessons in faith and socialism.

Recognizing her talent, Kollwitz's begetter arranged for her to begin lessons in drawing and copying plaster casts on 14 August 1879 when she was twelve.[x] In 1885-six she began her formal report of fine art under the direction of Karl Stauffer-Bern, a friend of the artist Max Klinger, at the Schoolhouse for Women Artists in Berlin.[11] At xvi she began working with subjects associated with the Realism motility, making drawings of working people, sailors and peasants she saw in her father'southward offices. The etchings of Klinger, their technique and social concerns, were an inspiration to Kollwitz.[12]

In 1888/89, she studied painting with Ludwig Herterich in Munich,[11] where she realized her strength was not as a painter, but a draughtsman. When she was seventeen, her brother Konrad introduced her to Karl Kollwitz, a medical educatee. Thereafter, Kathe became engaged to Karl, while she was studying fine art in Munich.[13] In 1890, she returned to Königsberg, rented her showtime studio, and connected to depict the harsh labors of the working course. These subjects were an inspiration in her piece of work for years.[fourteen]

In 1891, Kollwitz married Karl, who by this time was a doctor disposed to the poor in Berlin. The couple moved into the large apartment that would be Kollwitz'south home until it was destroyed in Globe War II.[xiv] The proximity of her married man'southward exercise proved invaluable:

The motifs I was able to select from this milieu (the workers' lives) offered me, in a simple and forthright way, what I discovered to be beautiful.... People from the bourgeois sphere were birthday without entreatment or interest. All middle-class life seemed pedantic to me. On the other paw, I felt the proletariat had guts. It was not until much later...when I got to know the women who would come to my husband for help, and incidentally too to me, that I was powerfully moved by the fate of the proletariat and everything connected with its way of life.... But what I would like to emphasize in one case more is that compassion and commiseration were at start of very niggling importance in alluring me to the representation of proletarian life; what mattered was but that I establish it beautiful.[15]

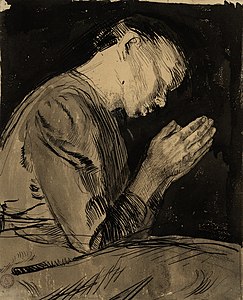

Woman with Dead Child, 1903 etching

Personal health [edit]

It is believed Kollwitz suffered anxiety during her childhood due to the decease of her siblings, including the early death of her younger brother, Benjamin.[sixteen] More recent research suggests that Kollwitz may have suffered from a childhood neurological disorder dysmetropsia (sometimes called Alice in Wonderland syndrome, due to its sensory hallucinations and migraines).[17]

The Weavers [edit]

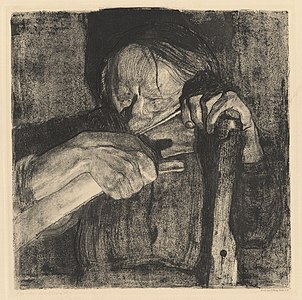

The March of the Weavers in Berlin

Between the births of her sons – Hans in 1892 and Peter in 1896 – Kollwitz saw a performance of Gerhart Hauptmann's The Weavers, which dramatized the oppression of the Silesian weavers in Langenbielau and their failed revolt in 1844.[xiv] [xviii] Kollwitz was inspired by the operation and ceased work on a series of etchings she had intended to illustrate Émile Zola's Germinal. She produced a wheel of six works on the weavers theme, three lithographs (Poverty, Decease, and Conspiracy) and three etchings with aquatint and sandpaper (March of the Weavers, Riot, and The Stop). Not a literal illustration of the drama, nor an idealization of workers, the prints expressed the workers' misery, hope, courage, and somewhen, doom.[18]

The bicycle was exhibited publicly in 1898 to wide acclaim. Simply when Adolph Menzel nominated her work for the aureate medal of the Keen Berlin Art Exhibition of 1898 in Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm Two withheld his approval, maxim "I beg you gentlemen, a medal for a woman, that would actually exist going besides far . . . orders and medals of honour vest on the breasts of worthy men."[nineteen] Nevertheless, The Weavers became Kollwitz' most widely acclaimed work.[20]

Peasant War [edit]

Kollwitz'southward second major bicycle of works was the Peasant War. The culmination of this series spanned from 1902 to 1908 due to many preliminary drawings and discarded ideas in lithography. The German Peasants' War was a violent revolution in Southern Frg in the early on years of the Reformation. Beginning in 1525, peasants who had been treated as slaves took arms against feudal lords and the church. Similar to The Weavers, this body of work might have been influenced by a Hauptmann drama, Florian Geyer. However, the initial source of Kollwitz's interest dated to her youth when she and her brother Konrad playfully imagined themselves as barricade fighters in a revolution.[21] Non but did Kollwitz have a babyhood connectedness, but an artistic connexion too. She was an advocate for those without a vocalization and liked to portray the working form in a way no ane else saw.[22] The artist identified with the grapheme of Black Anna, a woman cited every bit a protagonist in the uprising.[21] When completed, the Peasant War consisted of etchings, aquatints, and soft grounds: Plowing, Raped, Sharpening the Scythe, Arming in the Vault, Outbreak, The Prisoners and After the Boxing. After the Boxing is described as eerily premonitory every bit it features a mother searching through corpses in the night, looking for her son. In all, the works were technically more impressive than those of The Weavers, owing to their greater size and dramatic command of low-cal and shadow. They are Kollwitz's highest achievements every bit an etcher.[21]

Kollwitz visited Paris twice while working on Peasant State of war and enrolled in classes at the Académie Julian in 1904 in order to learn how to sculpt.[23] The etching Outbreak was awarded the Villa Romana prize. This prize provided a year's stay in 1907 in a studio in Florence. Although Kollwitz completed no work during her stay, she later on recalled the impact of early on Renaissance art she experienced during her fourth dimension residing in Florence.[24]

Modernism and World War I [edit]

Later her return to Deutschland, Kollwitz continued to showroom her work simply was impressed by younger compatriots. Expressionists and Bauhaus artists inspired Kollwitz to simplify her ways of expression.[25] Subsequent works such every bit Runover, 1910, and Self-Portrait, 1912, evidence this new direction. She also continued to work on sculpture.

Kollwitz lost her younger son, Peter, on the battlefield in World War I in October 1914.[26] The loss of her child began a stage of prolonged low in her life. By the end of 1914 she had fabricated drawings for a monument to Peter and his fallen comrades. She destroyed the monument in 1919 and began over again in 1925.[27] The memorial, titled The Grieving Parents, was finally completed and placed in the Belgian cemetery of Roggevelde in 1932.[28] Later on, when Peter's grave was moved to the nearby Vladslo High german state of war cemetery, the statues were also moved.

"We [women] are endowed with the strength to make sacrifices which are more painful than giving our ain claret. Consequently, we are able to see our ain [men] fight and dice when it is for the sake of freedom."[29]

In 1917, on her 50th birthday, the galleries of Paul Cassirer provided a retrospective exhibition of one hundred and 50 drawings by Kollwitz.[xxx]

Kollwitz was a committed socialist and pacifist, who was eventually attracted to communism. She expressed her political and social sympathies in her woodcut impress, "memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht" and in her interest with the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, a function of the Social Autonomous Party government in the starting time few weeks after the state of war. As the war wound down and a nationalistic appeal was made for sometime men and children to join the fighting, Kollwitz implored in a published statement:

There has been enough of dying! Let not some other homo fall![31]

While working on the sheet for Karl Liebknecht, she plant etching bereft for expressing awe-inspiring ideas. Later viewing woodcuts past Ernst Barlach at the Secession exhibitions, she completed the Liebknecht sheet in the new medium and made nearly 30 woodcuts by 1926.[32]

In 1919 Kollwitz was appointed to the position of professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts, the get-go woman to hold that position.[33] Membership entailed a regular income, a large studio, and a total professorship.[32] In 1933, the Nazi government forced her to resign from this position.[33]

In 1928 she was also named manager of the Master Class for Graphic Arts at the Prussian Academy.[26] Even so, this title would shortly be stripped after the Nazi regime rose to power.

War (Krieg) [edit]

In the years after World War I, her reaction to the war establish a continuous outlet. In 1922–23 she produced the cycle War in woodcut class, including the works The Cede, The Volunteers, The Parents, The Widow I, The Widow Ii, The Mothers, and The People.[34] Much of this art was inspired past pro-state of war propaganda which she and Otto Dix riffed on to create anti-war propaganda.[35] Kollwitz wanted to prove the horrors of living through a state of war to gainsay the pro-war sentiment that had begun to grow in Frg again.[36] In 1924 she finished her three most famous posters: Federal republic of germany'due south Children Starving, Bread, and Never Again State of war.[37]

Death Cycle [edit]

Working now in a smaller studio, in the mid-1930s she completed her last major cycle of lithographs, Death, which consisted of eight stones: Adult female Welcoming Death, Death with Girl in Lap, Death Reaches for a Grouping of Children, Decease Struggles with a Adult female, Expiry on the Highway, Death as a Friend, Death in the Water, and The Phone call of Death.

Seed Corn Must Non Be Ground (1942) [edit]

When Richard Dehmel called for more soldiers to fight in World War I in 1918, Kollwitz wrote an impassioned alphabetic character to the newspaper he published his call in stating that in that location should be no more than state of war, and that "seed corn must not be ground" in reference to young soldiers who were dying in the war.[38] In 1942, she fabricated a piece by the same name, this time in reaction to Earth State of war II. The work shows a mother, arms bandage over three young children to protect them.

The interior of Neue Wache in Berlin, with Käthe Kollwitz's sculpture Female parent with her Dead Son – centerpiece of what is today a memorial to "victims of war and dictatorship".

After life and World War II [edit]

In 1933, afterward the establishment of the National-Socialist regime, the Nazi Political party authorities forced her to resign her place on the faculty of the Akademie der Künste following her back up of the Dringender Appell.[39] Her work was removed from museums. Although she was banned from exhibiting, ane of her "female parent and kid" pieces was used by the Nazis for propaganda.[xl]

"They requite themselves with jubilation; they give themselves like a bright, pure flame ascending straight to heaven."[29]

In July 1936, she and her married man were visited by the Gestapo, who threatened her with abort and deportation to a Nazi concentration camp; they resolved to commit suicide if such a prospect became inevitable.[41] Yet, Kollwitz was by now a figure of international note, and no further activeness was taken.

On her 70th birthday, she "received over 150 telegrams from leading personalities of the fine art world," as well as offers to business firm her in the United States, which she declined for fear of provoking reprisals against her family.[42]

She outlived her husband (who died from an illness in 1940) and her grandson Peter, who died in action in World State of war II two years later.

Kollwitz-Schmidt burial plot in Berlin

She was evacuated from Berlin in 1943. Later that year, her house was bombed and many drawings, prints, and documents were lost. She moved start to Nordhausen, then to Moritzburg, a town near Dresden, where she lived her terminal months equally a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony.[42] Kollwitz died just xvi days before the end of the war.

Legacy [edit]

Kollwitz made a total of 275 prints, in etching, woodcut and lithography. Well-nigh the only portraits she made during her life were images of herself, of which there are at least fifty. These self-portraits institute a lifelong honest self-appraisal; "they are psychological milestones".[43]

Her silent lines penetrate the marrow like a cry of pain; such a cry was never heard among the Greeks and Romans.[44]

Dore Hoyer and what had been Mary Wigman's trip the light fantastic toe school created Dances for Käthe Kollwitz. The dance was performed in Dresden in 1946.[45] Käthe Kollwitz is a subject inside William T. Vollmann'south Europe Cardinal, a 2005 National Book Award winner for fiction. In the book, Vollmann describes the lives of those touched by the fighting and events surrounding Earth War 2 in Frg and the Soviet Matrimony. Her affiliate is entitled "Woman with Dead Child", after her sculpture of the same name.[ citation needed ]

An enlarged version of a similar Kollwitz sculpture, Female parent with her Dead Son, was placed in 1993 at the center of Neue Wache in Berlin, which serves equally a monument to "the Victims of War and Tyranny".[46]

More than forty High german schools are named after Kollwitz.[ commendation needed ] A statue of Kollwitz past Gustav Seitz was installed in Kollwitzplatz, Berlin in 1960 where it remains to this solar day.[47]

Four museums, in Berlin,[48] Cologne[49] and Moritzburg, and the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Koekelare are dedicated solely to her work. The Käthe Kollwitz Prize, established in 1960, is named after her.[50]

In 1986, a DEFA film Käthe Kollwitz, well-nigh the artist was made with Jutta Wachowiak as Kollwitz.[51]

Kollwitz is one of the 14 chief characters of the series 14 - Diaries of the Great War in 2014. She is played past actress Christina Große.[52]

In 2017, Google Doodle marked Kollwitz'south 150th birthday.[53]

An exhibition, Portrait of the Artist: Käthe Kollwitz was held at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England, from 13 September – 26 November 2017, and is intended to be shown subsequently in Salisbury, Swansea, Hull and London.[54]

Gallery [edit]

-

-

-

Whetting the Scythe, 1908, National Museum in Wrocław

Literature [edit]

- Hannelore Fischer for the Käthe Kollwitz Museum Cologne (Ed.): Käthe Kollwitz. A Survey of her Works. 1888 – 1942, Hirmer publishers, Munich 2022, ISBN 978-3-7774-3079-ix.

Run into also [edit]

- List of German language women artists

References [edit]

- ^ "Johanna Hofer, née Johanna Stern". knerger.de . Retrieved ane February 2022.

- ^ "KÄTHE KOLLWITZ". Orden Pour Le Mérite (in German language). Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Käthe Kollwitz at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Bittner, Herbert, Kaethe Kollwitz; Drawings, p. 1. Thomas Yoseloff, 1959.

- ^ Fritsch, Martin (ed.), Homage to Käthe Kollwitz. Leipzig: Eastward. A. Seeman, 2005.

- ^ "The aim of realism to capture the particular and adventitious with infinitesimal exactness was abandoned for a more abstract and universal conception and a more summary execution". Zigrosser, Carl: Prints and Drawings of Käthe Kollwitz, page Thirteen. Dover, 1969.

- ^ Schaefer, Jean Owens (1994). "Kollwitz in America: A Study of Reception, 1900–1960". Adult female's Fine art Journal. fifteen (1): 29–34. doi:10.2307/1358492. JSTOR 1358492.

- ^ Wirth, Irmgard (1980), "Kollwitz, Käthe", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 12, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 470–471 ; (full text online)

- ^ Rasche, Anna C. (1881). "Biographical Sketch of Dr. Julius Rupp". Reason and Religion by Julius Rupp. S. Tinsley & Company. p. 20. Retrieved vii Nov 2014.

- ^ Bittner, p. ii.

- ^ a b Rahim, Habibeh (1994). Capturing the Essence of their Vision and Class: A Treasury of Art Works by Women from the Hofstra Museum Drove. Hempstead, NY: Hofstra University.

- ^ Kurth, Willy: Käthe Kollwitz, Geleitwort zum Katalog der Ausstellung in der Deutschen Akademie der Künste, 1951.

- ^ Bittner, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Bittner, p. four.

- ^ Fecht, Tom: Käthe Kollwitz: Works in Color, p. vi. Random Firm, Inc., 1988.

- ^ Bittner, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Drysdale, Graeme R. (May 2009). "Kaethe Kollwitz (1867–1945): the creative person who may have suffered from Alice in Wonderland Syndrome". Periodical of Medical Biography. 17 (2): 106–10. doi:ten.1258/jmb.2008.008042. PMID 19401515. S2CID 39662350. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ^ a b Marchesano, Louis; Natascha, Kirchner (2020). Marchesano, Louis (ed.). Käthe Kollwitz: prints, procedure, politics. Los Angeles: Getty Research Plant. pp. 18, 30. ISBN978-one-60606-615-7. OCLC 1099544287.

- ^ Knafo, Danielle (1998). "The Dead Mother in Käthe Kollwitz" (PDF). Fine art Criticism. 13: 24–36 – via Danielleknafo.com.

- ^ Bittner, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Bittner, p. six.

- ^ Baskin, Leonard (1959). "4 Drawings, and an Essay on Kollwitz". The Massachusetts Review. 1 (1): 96–104. JSTOR 25086460.

- ^ Bittner, pp. half-dozen–vii. During this time she also visited Rodin twice.

- ^ "But there, for the first time, I began to understand Florentine fine art." Kollwitz, Kaethe: The Diaries and Messages of Kaethe Kollwitz, p. 45. Henry Regnery Company, 1955.

- ^ "Nevertheless I am no longer satisfied. At that place are besides many proficient things that seem fresher than mine... I should like to practice the new etchings so that all the essentials are strongly stressed and the inessentials almost omitted." Kollwitz, p. 52.

- ^ a b McCausland, Elizabeth (February 1937). "Käthe Kollwitz". Parnassus. 9 (2): 20–25. doi:10.2307/771494. JSTOR 771494 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Bittner, p. 9.

- ^ "I stood earlier the woman, looked at her—my ain face—and wept and stroked her cheeks." Kollwitz, p. 122.

- ^ a b Moorjani, Angela (1986). "Kathe Kollwitz on Cede, Mourning, and Reparation: An Essay in Psychoaesthetics". MLN. 101 (5): 1110–1134. doi:ten.2307/2905713. JSTOR 2905713.

- ^ "The elements of her nature and her fine art tin can often be felt more immediately in the drawings than in the prints, even much that in the latter has scarcely found a fulfillment." Kurth, Willy: Kunstchronik, N.F., Vol. XXXVII, 1917.

- ^ Kollwitz, p. 89.

- ^ a b Bittner, p. x.

- ^ a b "Käthe Kollwitz: About the Artist". National Museum of Women in the Arts . Retrieved 21 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Käthe Kollwitz and the Women of War | Yale University Printing". yalebooks.com . Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ Apel, Dora (1997). ""Heroes" and "Whores": The Politics of Gender in Weimar Antiwar Imagery". The Art Bulletin. 79 (3): 366–384. doi:10.2307/3046258. JSTOR 3046258. S2CID 27242388.

- ^ Sharp, Ingrid (2011). "Käthe Kollwitz's Witness to War: Gender, Authority, and Reception". Women in German Yearbook. 41: 193–221. doi:ten.5250/womgeryearbook.27.2011.0087. JSTOR x.5250/womgeryearbook.27.2011.0087. S2CID 142560257.

- ^ Bittner, p. 11.

- ^ Ingrid Sharp, "Käthe Kollwitz's Witness to War: Gender, Potency, and Reception," Women in German Yearbook 27, (2011): 95.

- ^ Dorothea Körner, "Man schweigt in sich hinein – Käthe Kollwitz und die Preußische Akademie der Künste 1933–1945" Berlinische Monatsschrift (2000) Issue 9, pp. 157–166. Retrieved 8 July 2010 (in German)

- ^ Kelly, Jane (1998). "The Signal is to Change It". Oxford Art Periodical. 21 (2): 185–193. doi:x.1093/oxartj/21.2.185. JSTOR 1360622.

- ^ Bittner, p. 13.

- ^ a b Bittner, p. xv.

- ^ Zigrosser, folio XXII, 1969.

- ^ Gerhart Hauptmann, quoted by Zigrosser, page XIII, 1969.

- ^ Partsch-Bergsohn, Isa (1994). Modern dance in Germany and the United States : crosscurrents and influences. Chur: Harwood Acad. Publ. p. 122. ISBN978-3-7186-5557-1.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (15 November 1993). "Berlin Periodical; The War Memorial: To Embrace the Guilty, Besides?". The New York Times . Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ 52°32′11″North 13°25′03″E / 52.5363839°N 13.4173625°Eastward / 52.5363839; xiii.4173625

- ^ Käthe Kollwitz Museum Berlin Official website. Retrieved 26 November 2017

- ^ Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln Official website. Retrieved xxx January 2011 (in German)

- ^ "Käthe Kollwitz Prize". Akademie der Künste, Berlin . Retrieved two Apr 2022.

- ^ Schall, Johanna (10 March 2011). "Theaterliebe: Interview mit Matthias Freihof zu "Coming Out"". Theaterliebe . Retrieved thirty January 2019.

- ^ Bopp, Lena (27 May 2014). "Das Leid, der Schmerz, die Angst sind stets gleich". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 10 Dec 2018.

- ^ "Käthe Kollwitz's 150th Birthday". Google Doodle . Retrieved ix July 2017.

- ^ "Ikon Portrait of the Artist: Käthe Kollwitz". Ikon Gallery. Retrieved 12 Nov 2017.

External links [edit]

campbellthole1960.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%A4the_Kollwitz

0 Response to "Where Did Kathe Kollwitz Study or How Did She Learn Art"

Post a Comment