What Various Methods Did the Byzantines Use to Hold Off Their Enemies?

The Byzantine army evolved from that of the tardily Roman period taking every bit leading models and shaping itself on the late Hellenistic armies,[1] but information technology became considerably more sophisticated in strategy, tactics and arrangement. The language of the army was still Latin, although later (peculiarly afterward the 6th century) Greek dominated, as information technology became the official language of the entire empire. Unlike the Roman legions, its strength was in its cavalry, particularly the armoured cataphracts, which evolved from the clibanarii of the late empire. Infantry were still used simply mainly as a base of maneuver for the cavalry, as well as in specialized roles. Most of the foot-soldiers of the empire were the armoured skutatoi and later on, kontarioi (plural of the singular kontarios), with the remainder beingness the light infantry and archers of the psiloi. The Byzantines valued intelligence and discipline in their soldiers far more bravery or brawn. The "Ρωμαίοι στρατιώται" were a loyal force composed of citizens willing to fight to defend their homes and their state to the death, augmented past mercenaries. The grooming was very much like that of the legionaries, with the soldiers taught close combat techniques with their swords, spears and axes, along with the all-encompassing do of archery.

Brief structural history [edit]

As the Byzantine empire's borders inverse, so did its armed services structure.

Over the course of its long history, the armies of Byzantium were reformed and reorganized many times. The only constants in its structure were its complexity and high levels of professionalism. During the 6th and 7th centuries, Hellenistic political systems, philosophies and eastern theocratic Orthodox doctrines,[2] had forced a greater simplification in the estate and administration that aimed to exercise the emperor's power in more direct means through his different's viceroys, in which civic and military powers would be personified in sigle entities with definitive powers, these beingness the future Byzantine, Strategos, Exarchs, Doux, Katepanos among others. The principal characteristics of a Theme were those of a constant source of income through the joint taxation liability organisation, which allowed a elementary management and counted with a corking military flexibility with the power to allow each Strategos to rapidly create provincial armies when needed.[3]

Despite having the aforementioned late Roman roots, the Byzantine Hellenophone east began to model its own warfare on the various Hellenistic war manuals known in the eastern Mediterranean, such as those of Arrian and Onosander,[iv] whose works enjoyed the aforementioned popularity as that of the Roman tactician and strategist Renatus Vegetius in Western Europe. Despite having Hellenistic roots, information technology was not a simple imitation of antiquity and information technology differed in several notable ways: Information technology had greater numbers of heavier cavalry, archers and other missile troops, and fewer Foederati. These differences may have been contributing factors to the eastern empire'due south survival. Information technology was with this Eastern Roman army that much of the western empire was reconquered in the campaigns of the generals Belisarius and Narses. Information technology was during this time, under Justinian I, that the revitalized empire reached its greatest territorial extent and the army its greatest size of over 330,000 men by 540. Later, under the general and emperor Heraclius, the Sassanid Empire of Persia was finally defeated.

Late in Heraclius' reign, however, a major new threat suddenly arose to the empire'due south security in the class of the Saracens. Spurred on by their new religion, Islam, which demanded the subjugation of the globe or its conversion to dar al-Islam,[v] and driven past a notwithstanding-strong tribal warfare mentality. Under the leadership of Khalid ibn al-Walid these invaders rapidly overran many of the empire's wealthiest and most important regions, particularly Syria, the Levant and Egypt.[vi] [ failed verification ] This new challenge, which seriously threatened the empire's survival, compelled Heraclius and his immediate successors, in the mid-7th century, to undertake a major reform of the Byzantine military system to provide for a more than cost constructive local defense of its Anatolian heartland. The result was the theme organization, which served as both authoritative and armed forces divisions, each nether the command of a military governor or strategos.

The theme was a division-sized unit of around ix,600, stationed in the theme (administrative district) in which it was raised and named for. The themes were not merely garrison troops, however, but mobile field forces capable of supporting neighboring themes in defensive operations, or joining together to form the backbone of an imperial expeditionary force for offensive campaigns. It was under this new system that the Byzantine army is more often than not considered to have come into its own, distinct from its belatedly Roman precursor. The thematic organisation proved to be both highly resilient and flexible, serving the empire well from the mid-7th through the late 11th centuries. Non only did it concord dorsum the Saracens, but some of Byzantium's lost lands were recaptured. The thematic armies also vanquished many other foes including the Bulgars, Avars, Slavs and Varangians, some of whom eventually concluded up in the service of Constantinople every bit allies or mercenaries.

In addition to the themes, there was also the fundamental imperial ground forces stationed in and virtually Constantinople called the Tagmata. The tagmata were originally battalion-sized units of guards and aristocracy troops who protected the emperors and defended the capital letter. Over time, though, their size increased to that of regiments and brigades, and more of these units were formed. The term thus became synonymous with the central field army. Due to growing military pressures together with the empire's shrinking economic and manpower base, the themes began to turn down. As they did so, the size and importance of the tagmata increased, due likewise to growing fears of the emperors over the potential dangers the strategoi and their themes posed to their power.

The concluding, fatal blow to the thematic army occurred in the aftermath of the disaster at the Boxing of Manzikert in 1071, when a new enemy, the Seljuk Turks, overran about of Asia Minor along with nigh of the empire's themes. In one case once more, the empire was forced to conform to a new strategic reality with reduced borders and resources. Under Emperor Alexios I Komnenos the themes were done away with and the war machine restructured effectually the tagmata, some of which were stationed in the provinces, but the bulk usually remained nearly Constantinople when not on campaign. Tagmata would henceforth have on yet a third meaning every bit a generic term for a standing military unit of regimental size or larger.

This tagmatic army, which includes those of the Komnenian and Palaiologan dynasties, would serve the empire in its final stages from the late 11th to the mid-15th centuries, a catamenia longer than the entire lifespans of many other empires. The tagmatic armies would likewise prove resilient and flexible, even surviving the near destruction of the empire in the backwash of the fall of Constantinople to the 4th Crusade in 1204. They would somewhen retake the capital letter for Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1261, and though reduced by then to a small strength, barely exceeding 20,000 men at most, would continue to defend the empire ably until the autumn of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. In no minor part due to increased reliance on mercenaries from the Latin west, the later on tagmatic armies would come to resemble those of western Europe at the fourth dimension, more than their Roman, Greek or Near-Eastern antecedents.

Infantry [edit]

Infantry types and equipment [edit]

Skoutatoi [edit]

twelfth-century fresco of Joshua from the monastery of Hosios Loukas. It accurately depicts the typical equipment of a heavily armed Byzantine infantryman of the 10th-12th centuries reassembling earlier Hellenistic militaristic patterns of the Eastern mediterranean. He wears a helmet, lamellar klivanion with pteruges and is armed with a kontarion and a spathion.

The majority of the Byzantine infantry were the skoutatoi (hoplite), named subsequently the skouton, a big oval, circular or kite-shaped shield. Their armor and weapons were modelled following ancient Seleucid and Hellenistic infantry equipment and patterns, which included:[7]

- Helmet: the helmet varied past region and time but was more often than not a simple, conical-shaped piece of steel, often with extra neck protection in the form of a mail aventail or padded coif.

- lōrikion (λωρίκιον): a mail or scale hauberk.

- klivanion (κλιβάνιον): Frequently associated with the characteristic Byzantine lamellar cuirass, it also referred to body armor in general. In add-on, pteruges (hanging leather strips) were frequently attached to protect the hips and thighs.

- epilōrikion (επιλωρίκιον): A padded leather or fabric over-garment, worn over the cuirass.

- kavadion (καβάδιον) or vamvakion (βαμβάκιον): A padded linen or wool under-armor, worn nether the cuirass.

- kremesmata: A heavy cloth brim hanging below a soldier's cuirass.

- kontarion (κοντάριον): a long spear (varied between ii.four and 4 k in length), the kontarion was used by the first ranks of each chiliarchia (battalion) in club to form a defensive Macedonian similar motorway wall.

- skouton (σκούτον): a large oval, circular (later kite-shaped) shield made of wood, covered by linen or leather and edged with rawhide, with a steel boss in before periods.

- spathion (σπαθίον): The typical Roman spatha, a longsword (about 70–eighty cm in length, depending on the menstruation) based on early Greek and Celtic blazon of swords; double-edged and weighing upwards to ane.6 kg (3.five lbs). Later on it referred to the medieval arming sword, usually with a crossguard curving back towards the handle.

- paramērion (παραμήριον): a one-edged sabre-like sword, girded at the waist.

Each unit had a dissimilar shield ornamentation often depicting earlier Hellenistic and contemporary Christian motifs. Unarmoured light infantrymen, oftentimes armed with javelins, were known every bit in Greek classical times as peltastoi and psiloi.

Toxotai and Psiloi [edit]

Like in earlier Greek states these composed the standard calorie-free infantry of the empire, in each chiliarchia they fabricated up the final three lines. These soldiers, highly trained in the fine art of bow were formidable archers and highly mobile units. Nigh of the Majestic archers came from Asia Pocket-size, peculiarly the region around Trebizond on the Black sea, where they were raised, trained and equipped.

Their equipment included:

- Blended bow

- kavadion

- spathion or tzikourion (small axe) for self-defence.

Although military machine manuals prescribed the use of light armour for archers, price and mobility considerations would have prohibited broad-scale implementation of this.

Varangians [edit]

The Varangian Guard was a strange mercenary strength and the aristocracy of the Byzantine infantry. It was composed principally of Norsemens, Nordic, Slavic and Germanic peoples, after 1066 information technology was increasingly English in limerick. The Varangians served as the babysitter (escort) of the emperor since the time of Basil Two, and were generally considered to be well-disciplined and loyal and so long as funds remained to pay them. Although near of them brought their weapons with them when entering the Emperor'south service, they did gradually prefer Byzantine military apparel and equipment. Their near feature weapon was a heavy axe, hence their designation equally pelekyphoros phroura, the "axe-bearing baby-sit".

Infantry organization and formation [edit]

Byzantine formations were adopted out of the earlier late Hellenistic armies, which applied the Macedonian and Seleucid phalanx often called chiliarchiai, from the Greek, chilia meaning one thousand, considering they had about 1000 fighting men. A chiliarchy was generally made up of 650 skutatoi and 350 toxotai. The skutatoi formed a line of 15-twenty ranks deep, in close order shoulder to shoulder. The first line was called the kontarion, the first four lines were made up of skutatoi the remaining three of toxotai. Three or four chiliarchiai formed a tagma (brigade) in the afterwards empire (after 750 AD) but chiliarchy-sized units were used throughout the empire'south life.[4]

The chiliarciai were deployed facing the enemy, with the cavalry on their wings. The infantry would counter-march to brand a refused heart, while the cavalry would hold or advance to envelop or outflank the enemy. This was similar to the tactic Hannibal employed at Cannae.

The chiliarciai were deployed non in the classic Roman checky Quincunx pattern merely in a Hellenistic long line with enveloping flanks. Each chiliarchy could presume different battle formations depending on the situation, the most mutual of these were:

- Line formation or phalanx, usually 8 men deep, which was generally used against other infantry or to repel a cavalry charge;

- Wedge, used to break the enemy's lines;

- Foulkon, like to the Roman testudo or Scandinavian shield wall, used to defend against heavy enemy missile burn down

- Parentaxis, with four ranks of armoured infantry in close social club in the front end, 4 ranks of armoured infantry in close club at the back and 4 ranks of archers in betwixt.[8]

Infantry tactics and strategies [edit]

Although the Byzantines adult highly sophisticated infantry tactics, the chief work of battle was done by cavalry. The infantry nevertheless played an of import role when the empire needed to demonstrate its forcefulness. In fact many battles, throughout Byzantine history, began with a frontal attack past the skutatoi with support from the horse archer units known as Hippo-toxotai (Equites Sagittarii).

During these assaults the infantry was deployed in the middle, that consisted of two chiliarchiai in wedge formation to intermission enemy'south line, flanked past two more than chilarchiai in a "refused wing formation" to protect the center and envelop the enemy. This was the tactic used past Nicephorus Phocas against the Bulgars in 967.

Each accuse was supported by toxotai that left the formation and preceded the skutatoi in guild to provide missile burn. Frequently, while the infantry engaged their enemy counterparts, the Clibanophori would destroy the enemy's cavalry (this tactic was used mainly against Franks, Lombards or other Germanic tribes who deployed armoured cavalry).

Byzantine infantry were trained to operate with cavalry and to exploit any gaps created by the cavalry.

An effective but risky tactic was to send a chiliarchia to seize and defend a high position, such as the top of a hill as a diversion, while the Cataphracts or Clibanophoroi, supported past the reserve infantry, enveloped the enemy's flank.

The infantry was ofttimes placed in avant-garde positions in front of the cavalry. At the command "aperire spatia", the infantry would open a gap in their lines for the cavalry to charge through.

Cavalry [edit]

Cavalry types and equipment [edit]

Kataphraktoi [edit]

The cataphract was an armoured cavalry horse archer and lancer who symbolized the power of Constantinople in much the aforementioned way equally the legionary represented the might of Rome.

The cataphract wore a conical-shaped helmet, topped with a tuft of horsehair dyed in his unit'southward colour. The helmet was often complemented by mail armour equally an aventail to protect the throat, neck and shoulders, which could likewise cover part or all of the face. He wore a hauberk of doubled-layered mail or scale armour, which extended downwardly to the knees. Over the hauberk, he would also wear a lamellar cuirass that could accept sleeves or non. Leather boots or greaves protected his lower legs, while gauntlets protected his hands. He carried a small, circular shield, the thyreos, bearing his unit of measurement's colours and insignia strapped to his left arm, leaving both easily complimentary to employ his weapons and control his horse. Over his mail shirt he wore a surcoat of lite weight cotton fiber and a heavy cloak both of which were also dyed in unit colours. The horses often wore barding of mail service or calibration armour with surcoats

The cataphract's weapons included:

- Composite bow: Same as that carried past the Toxotai.

- Kontarion: or lance, slightly shorter and less thick than that used past the skutatoi which could too be thrown similar a pilum.

- Spathion: Also identical to the infantry weapon.

- Dagger: Sometimes referred to as a "Machaira"

- Battle axe: Unremarkably strapped to the saddle as a backup weapon and tool.

- Vamvakion: Same every bit that of the infantry but with a leather corselet unremarkably depicted in ruby.

The lance was topped by a small flag or pennant of the aforementioned colour as helmet tuft, surcoat, shield and cloak. When not in use the lance was placed in a saddle kicking, much like the carbines of after cavalrymen. The bow was slung from the saddle, from which also was hung its quiver of arrows. Later Byzantine saddles, which included stirrups (adopted from the Avars), were an improvement over earlier Roman and Greek cavalry, who had used the four horned saddle without stirrups. The Byzantine state likewise fabricated horse breeding a priority for the Empire's security. If they could not breed enough high quality mounts, they would purchase them from other cultures.

The catafracti were cavalry regiments heavily armored riders and horses who fought in deployed column orders most effective against enemy infantry. Meanwhile, Clibanarii were also heavily armored horsemen, but were used primarily against cavalry. They employed a spear and shield and the horse's armor was changed from plate to leather, near often fighting in a wedge germination.[ix]

Lite Cavalry [edit]

The Byzantines fielded various types of calorie-free cavalry to complement the kataphraktoi, in much the same way as the Hellenistic kingdoms employed auxiliary light infantry to back up their heavily armored phalangites. Due to the empire's long experience, they were wary of relying too much upon strange auxiliaries or mercenaries (with the notable exception of the Varangian Guard). Regal armies unremarkably comprised mainly citizens and loyal subjects. The decline of the Byzantine armed forces during the 11th century is parallel to the pass up of the peasant-soldier, which led to the increased employ of unreliable mercenaries.[10]

Light cavalry were primarily used for scouting, skirmishing and screening confronting enemy scouts and skirmishers. They were likewise useful for chasing enemy lite cavalry, who were too fast for the Cataphracts. Low-cal cavalry were more than specialized than the Cataphracts, being either archers and horse slingers (psiloi hippeutes) or lancers and mounted javelineers. The types of light cavalry used, their weapons, armour and equipment and their origins, varied depending upon the time and circumstances. In the tenth century military treatise On Skirmishing explicit mention is made of Expilatores, a Latin word which meant "robber" or "plunderer" simply which is used to define a type of mounted sentry or lite raider. Also mentioned in descriptions of army- or thematic-level low-cal cavalry are trapezites, "those whom the Armenians call tasinarioi", who "should exist sent out constantly to charge down on the lands of the enemy, cause harm and ravage them."[11] Indeed, the discussion tasinarioi may be the linguistic antecedent to the mod word Hussar.

If the demand for light cavalry became swell enough, Constantinople would raise additional Toxotai, provide them with mounts and train them equally Hippo-toxotai. When they did use foreign light horsemen, the Byzantines preferred to recruit from steppe nomad tribes such as the Sarmatians, Scythians, Pechenegs, Khazars or Cumans. On occasion, they recruited from their enemies, such as the Bulgars, Avars, Magyars or Seljuk Turks. The Armenians were also noted for their low-cal horsemen, the tasinarioi.

Cavalry organization and formations [edit]

The Byzantine cavalrymen and their horses were superbly trained and capable of performing complex manoeuvres. While a proportion of the cataphracts appear to have been lancers or archers only, virtually had bows and lances. Their main tactical units were the numerus (likewise called at times arithmos or banda) of 300-400 men. The equivalent to the old Roman cohort or the mod battalion, the Numeri were usually formed in lines 8 to 10 ranks deep, making them almost a mounted phalanx. The Byzantines recognized that this formation was less flexible for cavalry than infantry but found the trade off to exist acceptable in exchange for the greater physical and psychological advantages offered past depth.

In the 10th century armed forces treatise attributed to Emperor Nikephoros II, On Skirmishing, it is stated that the cavalry ground forces of any mobile army allowable by the emperor must be of at least viii,200 riders, not including 1,000 household cavalry—that is, the force belonging personally to the Emperor. These 8,200 horse ought to be divided "into 24 units of up to 3 hundred men each. These twenty-four units, in plow, just as with the infantry, should make upwardly four groupings of equal strength, each with six combat units."[12] In such an organisation, the author of On Skirmishing argues, the army can keep on the march with these units "covering the iv directions, front rear and the sides."[12] So important was a large number of cavalry for operations against the Arabs that "if the cavalry army should finish up with an even smaller number [than 8,000 horse], the emperor must non prepare out on entrada with such a small number."[12]

When the Byzantines had to brand a frontal assault against a strong infantry position, the wedge was their preferred formation for charges. The Cataphract Numerus formed a wedge of around 400 men in eight to 10 progressively larger ranks. The first 3 ranks were armed with lances and bows, the rest with lance and shield. The first rank consisted of 25 soldiers, the second of 30, the third of 35 and the rest of 40, 50, 60 etc. adding ten men per rank. When charging the enemy, the first three ranks shot arrows to create a gap in the enemy'southward formation then at about 100 to 200 meters from the foe the first ranks shifted to their kontarion lances, charging the line at full speed followed by the residuum of the battalion. Often these charges ended with the enemy infantry routed, at this bespeak infantry would accelerate to secure the surface area and permit the cavalry to briefly rest and reorganize.

Cavalry tactics and strategies [edit]

As with the infantry, the Cataphracts adapted their tactics and equipment out of earlier Hellenistic treatises of war however this could variate in relation to which enemy they were fighting. In the standard deployment, 4 Numeri would be placed effectually the infantry lines. One on each flank with ane on the correct rear and another on the left rear. Thus the cavalry Numeri were not only the flank protection and envelopment elements just the main reserve and rear guard to protect the population and the Emperor.[13] [7]

The Byzantines usually preferred using the cavalry for flanking and envelopment attacks, instead of frontal assaults and almost always preceded and supported their charges with arrow fire. The front ranks of the numeri would draw bows and fire on the enemy'south front end ranks, then in one case the foe had been sufficiently weakened would draw their lances and charge. The back ranks would follow, drawing their bows and firing ahead equally they rode. This combination of missile fire with stupor activeness put their opponents at a grave disadvantage - If they closed ranks to better resist the charging lances, they would make themselves more vulnerable to the bows' fire, if they spread out to avert the arrows the lancers would have a much easier chore of breaking their thinned ranks. Many times the pointer fire and start of a charge were plenty to cause the enemy to run without the demand to close or melee.

A favorite tactic when confronted past a strong enemy cavalry force involved a feigned retreat and ambush. The Numeri on the flanks would charge at the enemy horsemen, then draw their bows plough around and fire as they withdrew (the Parthian Shot). If the enemy horse did not give hunt, they would continue harassing them with arrows until they did. Meanwhile, the Numeri on the left and correct rear would be fatigued upward in their standard formation facing the flanks and ready to assault the pursuing enemy as they crossed their lines. The foes would be forced to stop and fight this unexpected threat but as they did the flanking Numeri would halt their retreat, turn around and charge at full speed into their former pursuers. The enemy, weakened, winded and defenseless in a vice between ii mounted phalanxes would break with the Numeri they once pursued now chasing them. So the rear Numeri, who had ambushed the enemy horse, would motion up and attack the unprotected flanks in a double envelopment. This tactic is similar to what Julius Caesar did at Pharsalus in 48 BC when his allied cavalry acted every bit bait to lure the superior horse of Pompey into an deadfall past the vi aristocracy cohorts of his reserve "Quaternary line". The Arab and Mongol cavalries would also employ variations of information technology later to great effect when confronted by larger and more heavily armed mounted foes.

When facing opponents such equally the Vandals or the Avars with strong armoured cavalry, the cavalry were deployed behind the armoured infantry who were sent alee to engage the enemy. The infantry would attempt to open a gap in the enemy formation for the cavalry to charge through.

Byzantine Art of War [edit]

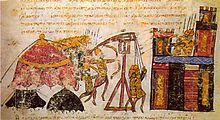

A siege by Byzantine forces, Skylintzes chronicle 11th century

Centuries of warfare enabled the Byzantines to write their own treatises on the protocols of war which somewhen contained strategies for dealing with traditional enemies of the state. These manuals enabled the wisdom of prior generations to find its style within newer generations of strategists.

One such manual, the famous Tactica by Leo VI the Wise, provides instructions for dealing with various foes such every bit:

- The Lombards and the Franks (the latter name was used to designate West Europeans in general) were defined as armoured cavalry which in a direct charge, could devastate an opponent. It was therefore advised to avoid a pitched battle confronting them. Still the textbook remarks that they fought with no discipline, lilliputian to no boxing club and more often than not had few if any of their horsemen performing reconnaissance ahead of the army. They as well failed to fortify their camps at dark.

- The Byzantine general was hence advised to best fight such an opponent in a series of ambushes and night attacks. If it came to boxing he should pretend to flee, drawing the knights to charge his retreating army - only to meet an ambush. It was too suggested that the Byzantine general should prolong the entrada and lure the enemy into desolate areas where an army could not live off the country, thus causing the "Frankish" army with its archaic logistics to fracture into many small foraging parties who could then exist defeated in detail.

- The Magyars and Patzinaks were known to fight as bands of lite horsemen, armed with bow, javelin and scimitar also as beingness accomplished in ambush and the use of horsemen to sentry alee of the army. In battle they advanced in small scattered bands which would harass the front line of the army, charging merely if they discovered a weak signal.

- The general was counselled to deploy his infantry archers in the front line. Their larger bows had greater range than that of the horsemen and could so continue them at a altitude. In one case the Turks, harassed past the arrows of the Byzantine archers, tried to shut into range of their bows, the Byzantine armoured cavalry would ride them down. Since nomads were known to employ the feigned flying stratagem the general was also cautioned against rash pursuit which could pb his army into ambushes. In a pitched battle he was brash to if possible anchor his position to rivers, ravines or marshes so as to preclude sudden rear of flank attacks past the highly mobile nomads. Terminal, if undertaking offensive operations, he was urged to practise so in late wintertime and early spring when the nomad'south horses were at their worst form after many months of little grass to eat.

- The Slavonic Tribes, such as the Serbians, Slovenes and Croatians still fought as human foot soldiers. However, the craggy and mountainous terrain of the Balkans lent itself to ambushes by archers and spearmen from above, where an regular army could be confined in a steep valley.

- Invasion into their territories was consequently discouraged, though if necessary, information technology was recommended that extensive scouting was to be undertaken in lodge to avoid ambushes; and that such forays were all-time undertaken in winter, where the snow could reveal the tribesmen tracks and frozen ice provide a secure path to otherwise difficult to accomplish marsh settlements. When hunting Slavonic raiding parties or meeting an ground forces in the field, it was pointed out that the tribesmen fought with round shields and footling or no protective armour. Thus their infantry should be easily overpowered past a charge of armoured cavalry.

- The Saracens were judged as the almost dangerous of all foes, as remarked by Leo VI: "Of all our foes, they have been the most judicious in adapting our practices and arts of state of war, and are thus the virtually dangerous." Where they had in earlier centuries been powered by religious fervour, by Leo 6's reign (886-912) they had adopted some of the weaponry and tactics of the Byzantine army. Saracen infantry on the other mitt was accounted past Leo VI to be little more than a rabble who lightly armed, could non lucifer the Byzantine infantry. While the Saracen cavalry was judged to be a fine force it lacked the discipline and organisation of the Byzantines, who with a combination of horse archer and armoured cavalry proved a mortiferous mix to the low-cal Saracen cavalry.

- Defeats beyond the mountain passes of the Taurus led the Saracens to concentrate on raiding and plundering expeditions instead of seeking permanent conquest. Forcing their style through a pass, their horsemen would charge into the lands at an incredible speed.

- The Byzantine general was to immediately collect a force of cavalry from the nearest themes and to shadow the invading Saracen army. Such a forcefulness might have been besides small to seriously challenge the invaders but it would deter detachments of plunderers from breaking away from the main army. Meanwhile the primary Byzantine army was to be gathered from all around Asia Minor and to meet the invasion force on the battlefield. Some other tactic was to cut off their retreat beyond the passes. Byzantine infantry was to reinforce the garrisons in the fortresses guarding the passes and the cavalry to pursue the invader, driving them up into the valley so equally to press the enemy into narrow valleys with little to no room to manoeuvre and from which they became easy casualty to Byzantine archers. A tertiary tactic was to launch a counter attack into Saracen territory as an invading Saracen force would often turn effectually to defend its borders should a message of an set on attain information technology.

- It was later added, in Nicephorus Phocas's armed services manual, that should the Saracen forcefulness only be caught up to by the time it was retreating laden with plunder then that the regular army's infantry should ready upon them at night from 3 sides, leaving the only escape the road back to their land. Information technology was deemed well-nigh likely that the startled Saracens would in all speed retreat rather than stay and fight to defend their plunder.

See also [edit]

- Byzantine army

- Byzantine navy

- Byzantine bureaucracy

- Byzantine military manuals

- Komnenian army

Notes [edit]

- ^ F. Schindler, Dice Überlieferung der Strategemata des Polyainos (Vienna 1973) 187–225; E.L. Wheeler, "Notes on a Stratagem of Iphicrates in Polyaenus and Leo Tactica", Electrum 19 (2012) 157–163.

- ^ Dvornik, Francis (1966). Early Christian and Byzantine political philosophy : origins and background. OCLC 185737639.

- ^ "Historians and the Economy: Zosimos and Prokopios on Fifth- and 6th- Century Economie Evolution", Byzantine Narrative, BRILL, pp. 462–474, 2017-01-01, retrieved 2022-03-13

- ^ a b Dain, Alphonse (1930). Les Manuscrits d' Onésandros. Les Belles Lettres. OCLC 421178980.

- ^ Ye'or, Bat (1996). The Pass up of Eastern Christianity Under Islam: From Jihad to Dhimmitude: Seventh-Twentieth Century. Miriam Kochman, David Littman (trans.). Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 522. ISBN978-1-61147-136-6.

- ^ Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. p. 316. ISBN0-521-52940-9.

- ^ a b A. Dain, Les manuscrits d'Onésandros (Paris 1930) 145–157

- ^ "Some Aspects of Early on Byzantine Artillery and Armour", Byzantine Warfare, Routledge, pp. 391–406, 2017-03-02, ISBN978-1-315-26100-3 , retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ Wojnowski, M. "Periodic Revival or Continuation of the Aboriginal War machine Tradition? Another Look at the Question of the KATÁFRAKTOI in the Byzantine Regular army". Studia Ceranea. Journal of the Waldemar Ceran Inquiry Centre for the History and Culture of the Mediterranean Area and Due south-Due east Europe, vol. 2, Dec. 2012, pp. 195-20, doi:10.18778/2084-140X.02.xvi. (197-198)

- ^ "The Varangian Guard", Byzantine Narrative, BRILL, pp. 527–533, 2017-01-01, ISBN978-ane-876503-24-6 , retrieved 2021-05-29

- ^ Nikephoros Phokas, On Skirmishing, Ch. 2, in George T. Dennis (ed.), 3 Byzantine Military machine Treatise, (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2008), p. 153.

- ^ a b c George T. Denis, Three Byzantine Military Treatise, (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2008), p. 275.

- ^ George), Dawson, Timothy (Timothy (2009). Byzantine cavalryman, c.900-1204. Osprey. ISBN978-i-84603-404-6. OCLC 277201890.

References [edit]

- Dennis, George T. (1984). Maurice's Strategikon. Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy . Philadelphia, PA: Academy of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN0-8122-1772-1.

- Dennis, George T. (1997), "The Byzantines in Boxing", in Tsiknakis, K. (ed.), Byzantium at War (9th–12th c.) (PDF), National Hellenic Enquiry Foundation - Centre for Byzantine Research, pp. 165–178, ISBN960-371-001-six, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-06

- R.E. Dupuy and T.N. Dupuy (2nd Revised Edition 1986). The Encyclopedia Of Military History: From 3500 B.C. To The Present.

- Haldon, John F. (1997), "The Organization and Back up of an Expeditionary Force: Manpower and Logistics in the Middle Byzantine Period", in Tsiknakis, Thou. (ed.), Byzantium at War (9th–twelfth c.), National Hellenic Enquiry Foundation - Middle for Byzantine Research, pp. 111–151, ISBN960-371-001-6 [ permanent dead link ]

- Haldon, John (1999). Warfare, Land and Lodge in the Byzantine Globe, 565–1204. London: UCL Press. ISBN1-85728-495-X.

- Haldon, John F. (2001), The Byzantine Wars, Tempus, ISBN978-0-7524-1795-0

- Kollias, Taxiarchis 1000. (1988), Byzantinische Waffen: ein Beitrag zur byzantinischen Waffenkunde von den Anfangen bis zur lateinischen Eroberung (in High german), Vienna: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN3-7001-1471-0

- Kollias, Taxiarchis M. (1997), "Η πολεμική τακτική των Βυζαντινών: Θεωρία και πράξη", in Tsiknakis, K. (ed.), Byzantium at War (ninth–12th c.), National Hellenic Research Foundation - Centre for Byzantine Research, pp. 153–164, ISBN960-371-001-half-dozen

- Lazaris, Stavros (2011), "Rôle et place du cheval dans l'Antiquité tardive : Questions d'ordre économique et militaire", in Anagnostakis, I.; Kolias, T. G.; Papadopoulou, E. (eds.), Creature and Environment in Byzantium (7th-twelfth c.), National Hellenic Research Foundation - Centre for Byzantine Enquiry, pp. 245–272, ISBN978-960-371-063-nine

- Lazaris, Stavros (2012), Le cheval dans les sociétés antiques et médiévales. Actes des Journées internationales d'étude (Strasbourg, 6-7 novembre 2009), Brepols, ISBN978-ii-503-54440-3

- McGeer, Eric (1995), Sowing the Dragon's Teeth: Byzantine Warfare in the Tenth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Studies 33, Washington, D.C.

- McGeer, Eric (1988), "Infantry versus Cavalry: The Byzantine Response", Revue des études byzantines, 46: 135–145, doi:ten.3406/rebyz.1988.2225, retrieved 28 May 2011

- Oman, Charles (1960). The History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages (Revised ed.). Cornell Academy Printing. ISBN0-8014-9062-6.

- Rance, Philip, 'The Fulcum, the Late Roman and Byzantine Testudo: the Germanization of Roman Infantry Tactics?' in Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 44.3 (2004) pp. 265–326: https://web.archive.org/web/20121013035512/http://world wide web.duke.edu/spider web/classics/grbs/FTexts/44/Rance2.pdf.

- Rance, Philip, 'Drungus, DROUNGOS, DROUNGISTI, a Gallicism and Continuity in Late Roman Cavalry Tactics, Phoenix 58 (2004) pp. 96–130.

- Rance, Philip, 'Narses and the Battle of Taginae (Busta Gallorum) 552: Procopius and sixth-century Warfare', Historia 54/4 (2005) pp. 424–72.

- Sullivan, Dennis F. (2000). Siegecraft: 2 Tenth-century Instructional Manuals . Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN0-88402-270-6.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Social club. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN0-8047-2630-ii.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1998), Byzantium and Its Army, 284–1081, Stanford University Press, ISBN0-8047-3163-two

campbellthole1960.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_battle_tactics

0 Response to "What Various Methods Did the Byzantines Use to Hold Off Their Enemies?"

Post a Comment